By Steve Dawson

It is a privilege to be able to write about my family’s ancestral Japanese roots, especially given the significance of Sakuragawa Rikinosuke, who is recorded as the first Japanese to settle in Australia. Technically, this pioneer was my great- great-grandfather, but the bloodline actually begins with his son, Ewar Dicinoski (Togawa Iwakichi), who was seven when they arrived in Australia in 1873.

We are stil unsure whether Ewar was Sakuragawa’s biological or adopted son, or his protégé. Nevertheless, they were ‘father and son’. Sakuragawa also brought his 10-year-old daughter, Makichi Sakuragawa Ume, but she returned to Japan in 1875. Sakuragawa Rikinosuke is reported to have been born in Edo (former name for Tokyo ) in 1848, and Togawa Iwakichi was born in Edo in December 1865.

Japan had barely begun to engage the West under the Meiji Restoration, following the overthrow of the Tokugawa Shogunate that ruled during the Edo Period. At this time, there was a policy known as sakoku, which controlled international travel and trade by Japanese. However, this was repealed in 1866, and passports were issued for purposes of study and trade. Interestingly, under a loophole in Japan’s strict rules on the issuing of passports, foreign entrepreneurs were able to endorse and support passport applications for numerous Japanese acrobats to travel and perform abroad.

Research shows passports were issued by Yokohama prefectural authorities on 7 October 1872 to Sakuragawa Rikinosuke and Togawa Iwakichi. The next day, 8 October 1872, they departed Yokohama on aboard P & O’s Avoca (headed for London via Kolkata, formerly Calcutta, India), and appear to have been in the employment of French entrepreneur C. Pasquale. Subsequently, they departed Calcutta under the employment of Thomas King, and arrived in Sydney aboard the R.M.S. Baroda on 29 July 1873. They were part of a group of 13 Japanese performers, and were accompanied by King. Actually, the R.M.S. Baroda manifest for that day lists ‘Mr and Mrs King with 18 Siamese troupe’.

After performing across Australia and New Zealand, Sakuragawa married Jane Kerr in 1876 in Fitzroy, Melbourne, one of few Japanese immigrants to marry an Australian. For the next few years, Sakuragawa raised a family and continued to work as a circus performer and travelled around Australia from town to town. In 1882, he decided to settle and take up farming in Herberton, Queensland, and applied to be naturalised in order to secure a homestead on Crown land – this marked his entry into the history books as the first Japanese settler in Australia. The farming venture did not work out, so Sakuragawa went back to being an acrobat. Unfortunately, he died in June 1884 from tuberculosis and was buried at Rookwood Cemetery in Sydney.

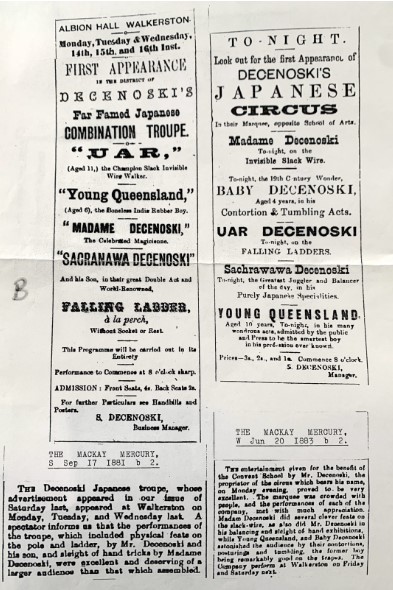

Circus flyers and newspaper-reviews of Sakuragawa Decenoski’s circus troupe performances (circa 1881, 1883)

Upon arriving in Australia, the name Rikinosuke was phonetically recorded as ‘Decenoski’, which became the name used thereafter by Sakuragawa until his death. In fact, he was recorded as using ‘Sacarnawa Decenoski’ for most circus performances, and he also adopted ‘Reginald’ as an English first name. His son, Ewar, also used ‘Decenoski’, but after Sakuragawa’s death, changed this to ‘Dicinoski’, which was recorded officially upon his marriage on 20 February 1892, at the age of 26. Ewar married Susan Bowtell, who was 16 years old in Warracknabeal, and they went on to have 11 children, though sadly, two died quite young. One of them, Ewar junior, was my grandfather, who was affectionately known as ‘Hughie’ (another variation of Ewar, whose origins lie in ‘Iwakichi’).

Having joined numerous circus troupes, including Ashton and St Leon, Ewar senior eventually established the ‘Dicinoski Troupe’ in 1900, which consisted of his growing family. They travelled to all states of Australia. The unique surname ‘Dicinoski’ – only found in this bloodline from Sakuragawa Rikinosuke and Togawa Iwakichi – remains to this day, and was my mother’s maiden name.

For many reasons, the Japanese lineage has been a curious question in recent years in my family. It was once investigated by one of my aunties, but in a non-globalised and non-digital world. Things seemed to come to a halt also with the untimely passing of a key ANU researcher, Dr David Sissons, who was a skilled proponent of knowledge about the Japan–Australia relationship, and was fascinated with our family connections as they related to the commencement of culturally significant bilateral relations. Most of the records that I have are testimony to the excellent research efforts made by David Sissons.

I would like to say that interest in our Japanese lineage has always been strong in our family, but this is not the case. In fact, I do not recall this ever being a topic of conversation while I was growing up and well into my young adult life. The truth is, my mother and her sisters were quite proud to be from northern Queensland (Delulu, Mount Morgan, Rockampton) and to be ‘simple country’ people, and they did not speak of their Japanese origins, for they were simply not aware of them.

The growing Dicinoski family: Ewar, Susan and children Amelia, Ewar Junior, Goldie, Pearlie, Joey, Billy and Norman.

My grandfather, Ewar ‘Hughie’ Dicinoski, after being raised as a circus performer with the Dicinoski Troupe to about age 20, worked as a stockman, jockey, and horse breaker for most of his adult life. I wondered if at some point, there was a conscious or unconscious decision, or perhaps just a natural transition, to overlook or suppress our ancestral Japanese roots, and I felt compelled to question my mother about it. She responded that they never asked about their father or mother’s family history, as it ‘was just not done; it was a different age back then. You certainly did not ask such questions of your parents.’ I asked if they, or others in the community, were ever curious about their father’s obvious Asian appearance, as he was half Japanese, but none were. I queried why did they think their father never told them about the family’s Japanese history, and they gave the same response: ‘It was just not done.’

In fact, according to my mother, the first that any family member knew of our Japanese ancestry was when one of their uncles, Reginald – Ewar and Susan’s first child – was contacted in the 1970s in relation to official records. For me, this is astounding, and somewhat saddening at the same time. And I lament the loss of historical family information that could have been passed on and shared. The key to the family’s lack of knowledge about ancestral Japanese roots lay with Ewar Dicinoski.

Noting the realities of historical events and the White Australia policy, I wondered if the ‘Japanese-ness’ was suppressed intentionally by great-grandfather Ewar Dicinoski, so that he and his large family could simply be ‘Australians’. My mother believes this could be a distinct possibility, but common sense provides another explanation. Ewar was only seven years old when he arrived in Australia, so he essentially grew up in Australia like any other Australian child. Linguistically, he could have been bilingual if he had maintained his Japanese language, but this seems not to be the case. His relationship with his adopted father, Sakuragawa Rikinosuke, remains a mystery. For all intents and purposes, Ewar was a country person with a country accent, but looked Asian. However, my research revealed that a time came when Ewar faced his Japanese heritage and felt the need to take action.

Japan entered World War I in August 1914 on the side of the Entente Allies, and quickly took control of German territories in the Pacific and mainland China. But it had already aroused European/Western interest and suspicion after decisively defeating Russia in the Russo-Japanese War between 1904 to 05, the first such victory by an Asian nation.

Interestingly, my search of records at the National Archives of Australia reveal that Ewar Dicinoski applied to External Affairs in September 1914 to become naturalised under the Naturalisation Act 1903. He was rejected on these grounds: ‘you are an Aboriginal native of Asia and you are not eligible to become naturalised under the Commonwealth.’ Perhaps the trigger for this application was the commencement of WWI in June 1914, and possibly the influence of stricter immigration policies up to that time, which began with the White Australia policy 1901 (with the Immigration Restriction Act 1901 as a foundation) that sought to reduce the numbers of immigrants,Asians in particular.

At that time, Ewar was 48 years old, had eight children, and his profession was ‘travelling acrobat’. Certainly, he had no fixed address and acknowledged that he did not know his exact birth date or the details of his arrival in Australia. He was subsequently registered as a ‘Japanese alien’ in 1917 under War Precautions (Alien Registration) Regulations 1916. We know from the written description on these documents that he was five feet one inch, had black hair and brown eyes, a scar on his right temple, and was of ‘strong, nuggety build’.

Of course, with the advent of Japan’s expansionist policies in the Pacific and the outbreak of World War II, the Dicinoski family may well have been concerned about their well-being. But Ewar actually died in September 1938, and Ewar’s children were adults by then, and may still have been unaware of their true roots, or continued their father’s wish to suppress knowledge of these roots, including their Japanese acrobatic lives. It appears that even when addressing the reality of his Japanese status in 1914 at the age of 48, Ewar may have chosen at that time to not communicate his heritage to his children. We may never know the reason for this, and can only surmise it was because, essentially, he did not ‘feel’ Japanese, and did not want his family to be alienated, as he may have felt by the denial from External Affairs, and simply wanted to continue living without discrimination.

It appears that Dicinoski family members’ knowledge of the significance of Japanese roots did not become apparent until they were researched deeply by Dr Sissons. Despite not being discussed openly, the Japanese genes are strong, I think, and are apparent in Dicinoski’s descendants. My mother, like her three sisters, all had black hair in their youth, dark brown eyes, and olive skin. My older brother has the same features. We are somewhat ‘height challenged’. I am the tallest in our nuclear family at 168 cm, and I recall my grandfather was 15 cm and his twin sisters – Pearlie and Goldie – were abuot the same height.

Aunty Goldie and Aunty Pearlie when they were younger, with Grandpa Hughie behind them.

As children in Ewar senior’s (Togawa Iwakichi) circus, they were acrobats and contortionists, among other roles. One of Ewar’s apparently unique acts was performed on an invisible slackwire using a piano wire! Throughout my life, I have had an inexplicable affinity for all things Asian: my wife is Filipina by birth, I am a very good linguist – Chinese, Indonesian, though sadly, not Japanese – and I have lived and worked in Asian countries. A passion in my current life is helping non-native speakers learn English professionally and informally. Oddly, my mother and brother do not share this affinity with Asia and Asian cultures, despite having more ‘Asian’ physical features. Even though we’re related, my brother and I do not look alike. Remarkably, my interest may also be strongly influenced by my father, who has an Anglo-Saxon heritage and was an academic who taught Chinese and Vietnamese at Griffith University in Queensland.

As a teenager and young man, I recall from time to time visiting great Aunties Goldie and Pearlie in Brisbane. They lived practically their entire lives together, except for a few years when Goldie was married. In a word, they were ‘cute’, and quite inseparable. As they aged, Pearlie lost her eyesight, and Goldie lost her hearing, and they continued to function as one pair, complementing each other. Although not identical twins, I was mesmerised at how they knew each other’s thoughts, and always began and ended sentences in harmony.

In hindsight, had I been aware of the family’s roots, I would have been inclined to delve deeper and ask many questions, but I was blinded by their quietness, selflessness, and aversion to talking about themselves. It seems obvious, now, that they may not have known very much about their Japanese father’s story either, but the most recent family-sourced information suggests all of Ewar’s children were aware of their Japanese heritage, but upheld the lifelong agreement to conceal these roots.

I remember only seeing my grandfather, Ewar (‘Hughie’) Dicinoski a few times, as he lived a sedentary life and I, like my father and brother, was in the military and moved around quite a bit. The last time I saw him was in the early 1980s. Grandpa Ewar Junior’s demeanour and personality was exactly like his sisters’ Pearlie and Goldie. He was quietly spoken, with a Queensland country accent and manner. He smiled warmly and easily, and his eyes always smiled too. He looked cute and Yoda-like with grey wisps of hair on his balding head. Despite not knowing me well, I felt that Grandpa was equally proud of me as he was of his other three grandchildren, but I sensed that my world was far removed from his and clearly generations apart.

Grandpa was tough. I recall that he had tolerated a headache for a couple of days, which he put down to another redback spider bite on the outside ‘throne’! I will always remember the sight of this diminutive man as an 80 plus year old horse whisperer of sorts, breaking in a wild horse. His skin was tanned and leathery from years working under the Queensland sun, but I once walked in on him while he was changing his shirt and was astonished to see pale white skin on the torso of a fit man 60 years his junior.

Sadly, after a long, healthy life in the country, independent of medicines that most people take regularly and for granted, Grandpa Ewar had a mild heart attack, entered Rockampton Hospital and passed away in 1985, perhaps prematurely, at the age of 87.

All photos courtesy of Dawson Family archives unless otherwise stated. This includes historical photographs donated to the family by the late D. C. S. Sissons.

What a fabulous story from one prewar Nikkei family to the oldest. Thank you for sharing.

Hi Steve,

One of Ewar’s children is not mentioned here, Norman. My husband is descended through Norman. Norman’s son is Henry Dicinoski (of Rockhampton), Henry’s son is Gavin (of Sunshine Coast), Gavin’s son (my husband) is Matthew (of Seattle, WA, USA) and we have two sons. Thank you so much for posting this and all the detailed history. I find my husband’s Japanese roots very interesting and have done my own research as well (Ancestry.com).

Cheers from the U.S.

-Marylyn Dicinoski

Hi Marylyn. Wow! The Dicinoski clan certainly stretches far and wide. Thank you for your wonderful feedback, and good on you for showing interest in Matthew’s family roots. I hope to be able to explore the Japan-side of the story at some point, and will be happy to keep you informed.

Nikkei will forward my email address to you.

Kind regards,

Steve

Thank you for your kind comments, Andrew.

From one Nikkei Australian to another I enjoyed learning about your family history. I was aware of your family as when at university in the late 1970s and early 80s I met David Sissons and he shared his various articles with me. So glad to know you embrace your Nikkei heritage.

Hi Steve, my husbands 3rd great granddad is rikinosuke so he is direct dependant from rikinosuke, not ewar, I have my husbands grandma visiting us in loganlea qld from Cairns on the 26th may 2023, with documents on her side of the family for family tree day, would someone from yours be available for morning too than day? Please contact me asap on 0467792082, we would like to try and trace back to Japan for mikoto family if possible as we travelled there a few times before we knew about the lineage (wasn’t till after we got married in 2022 that I saw the news paper clippings etc and made the connextions)

Hi Zoe. I have left a message on the mobile phone number provided. Awaiting your reply. Thanks!

This is fascinating, I love the details in this story. Such a moving account. Thanks for sharing this story Steve, and the photos are fantastic too.

I had known about Sakuragawa Rikinosuke from Dr Yuriko Nagata, and to see his story come to life like this in your family narrative feels so special.

Thank you very much, Masako. Such lovely comments and feedback. It was quite a therapeutic, riveting and enjoyable experience to finally document – albeit it briefly – the family history. Personally, I look forward to the next chapter of exploring the Japanese side, which includes Sakuragawa Rikinosuke’s background, and especially the roots of my great-grandfather, Togawa Iwakichi, and how he came to be his adopted son.

Sorry for my late reply, Andrew. You are so lucky to have met Prof. Sissons – he sounds like an extraordinary individual, who I am sure is sadly missed.

Hi Steve,

I was married to a son of another of Ewar’s children who isn’t named in this article. This was Cecil Oscar who was born in Miles and died in Blackall in 1962. Cecil married Ellen Jean Rose and they had 9 children Hope, William(Billy), Beverly, Raymond, Gordon, Victor, Neville, Alana and Geoffery who lived to adulthood. One of my children is now a Japanese teacher based in Mackay. I have done quite a bit of research into this side of the family for my children and grandchildren. It is interesting that Gordon insisted that the family were of Russian descent. I would also love to hear more of the roots of Togawa Iwakichi so I can inform my children and grandchildren.

All the best Kate.

Hi Kate. Thank you for sharing that wonderful family information. Clearly, like roots and branches of a tree, the Dicinoski family stretches far and wide, and many descendants may be unaware of the true family origins. It is interesting that your husband, Gordon, believed in Russian descent, and I can relate to this. As a child, i was told by my parents that we had a mixture of Polish and British blood. The Polish assumption was based on the ending of ‘DicinoSKI’ (the suffix ‘~ski’ in Polish means ‘from’, much like ‘da’ in Italian, e.g., Leonardo da Vinci; my wife and I visited the fascinating town of Vinci in Northern Italy a few years ago!). This logical fallacy about ‘~ski’ prevailed in the absence of factual knowledge.

I, too, look forward to uncovering the Togawa Iwakichi side of our family history.

Take care!

Hi Steve. Regrettably, I am only distantly related to your family by marriage. Reginald Dicinoski married Bridgette O’Brien (always known as Ann), my father’s aunt. My parents were very close to Ann and Reg, and we often visited them at their house in Coorparoo, Brisbane. We remember Reg as a small, quiet man who owned a little Morris or something – a ute. He was some kind of tradesman. He looked rather like Gandhi, in fact!

Personally, I lived in Japan for many years, and worked for a Japanese company. When I returned to Australia, I took my PhD in Japanese history, and corresponded with Sissons and Neville Meaney. I wish I had known the Dicinoski story then!

I would love to know of you have made any progress in your investigations into Sakuragawa Rikinosuke’s history. Regards, Ben.

Hi Ben,

Apologies for my late response. Thank you for your fascinating comment. I do envy you the Japanese experience and studies, and certainly that you corresponded with Sissons (such a loss). Of course, I will provide an update into the Japanese side of this story in due course.

Kind regards. Steve

Hi

My I’m Jennifer McBride. I grew, up in Brisbane, my Grandmother, Violet Oliver, was a child of a Japanese circus entertainer. Stories about my Grandmother’s life were hard to come by, one I remember being told, was she was born on a circus train. Sadly I’m not sure if this is fact or fiction.

I was fascinated by your story. I have, so many questions regarding the historical significance of the early circus entertainers relating to my own family heritage.

I did, see photo’s of my Great Grandfather, my sister contacted a professor, I’m no longer in touch with my sister, so not sure if the Professor name is Sisson?, But the contact knew a lot about the Japanese acrobatic troupe and circus.

Do you have more information regarding Professor Sisson.

I would Appreciate any information, about early Japanese acrobatic circus.

Thank you

Kindest regards, Jennifer McBride

Hi Jennifer,

Violet is my great grandmother. She had a daughter Beatrice, my grandmother.

Hi Steve,

I would love to get into contact with you.

I believe my mother and Aunty would catch up with your mum and aunties.

My great grandmother is Violet Beatrice. Daughter of Sacarnawa decenoksi and Honora Jane (Kerr).

I’m so fascinated with our families history. I have lots of photographs, certificates, clippings that my grandmother left us.

Please do get in touch!

Hi Danielle, We are related through my great grandmother Honora Jane Kerr. Two years after her husband’s death she married my great grandfather Sylvanus Pierpont Statham in1886. My mother also called Violet told stories of when the circus came to town their family entertained circus members. I assume they were members of the Decenoski

Hi Kathy. Many thanks for reaching out to Danielle. I will contact you both soon via email.

Kind regards,

Steve

Hi Kathy!

This is so interesting.

Would love to get into touch with you and learn more about Honora Jane Kerr.

My grandmother is Ruby Beatrice and her mum was Violet Beatrice (Jane Kerr daughter)

Hi Danielle. Thanks for your additional comment. I see that you’ve found a bloodline relative in Kathy! I will contact you both by email.

Kind regards,

Steve

Hello Jennifer. Do you have more information about your grandmother – ‘Violet Oliver’? Is it possible that her maiden name was ‘Amelia Violet Dicinoski’, and ‘Oliver’ was her married surname?

Thanks.

Steve

Hello Steve,

I am a descendant of Ewar Dicinoski, my great grandfather Cecil is Ewar’s son making Ewar my great great grandfather. I would love to get in contact with you in regards to our family tree.

Hi Tayla!

Most interesting – a distant relative ☺️ Please do not hesitate to email me.

Steve

Hi Steve,

I believe the rest of Iwakichi’s family was as follows:

Joseph February 1904 Glen Innes

Edgar ” ” ” ” (died 1905)

Hector October 1906 Inverell

Norman December 1909 Blackall

Cecil Oscar March 1914 Miles

Ewar died on 3 September 1938 at Dunwich on North Stradbroke Island and was buried at Toowong Cemetery, Brisbane.

I also suggest that the photo labelled “Sakuragawa Rikinosuke and wife Jane Kerr (circa 1875-6)”

is of the wedding of Iwakichi’s colleague Ichitaro.

Kind regards,

John (johnlamb@netspeed.com.au)

Thank you for your story’ My grandfather joined a Japanese circus when he was about about 9 years old when the circus visited Adelaide we are not sure if the circus is the same one we have a picture of my grandfather sitting on a ring being held up by a young member of the troupe with a another member standing by this photo was left behind by my grandfather and he said it was him in the hoop

June Carey

Hi June. Thanks for your comment. I am not sure how many purely ‘Japanese’ circuses there are/were active in Australia, but that would be interesting to know. I gather your grandfather would have had many interesting experiences and stories.

Take care.

Steve

Hi Steve,

I’m a journalist at ABC Brisbane and I’m hoping to get in touch with you to write an article about Sakuragawa Rikinosuke. Please get in touch.

Hi Steve I am a granddaughter of Cecil Oscar and Ellen Jean Rose. My father is Victor Dicinoski my father was also lead to believe we were of Russian decent. I just read Kate’s comment just missing a few kids there was also Claude and Robert that are my father’s brothers. Uncle Claude Uncle Geoffrey and Aunty Lana all live in the same town not far from where I live. My father currently lives in Rockhampton. It was very interesting to read this article my dad had told me growing up that his family were in the circus and also that their name had been changed but the reasons why was unknown. My 3 sister’s and I all have the short Dicinoski gene I’m 156cm and am the tallest out of my sister’s. Thanks for the great read my daughter’s and I loved it.

Hi Priscilla. How interesting that you, like Kate, were told of Russian heritage as offspring of Cecil Oscar – the impact of concealed Japanese heritage in the Dicinoski clan is widespread. I am very pleased that you and your daughters enjoyed the article. The continuing feedback and comments triggered by this article encourage me to do what I can to investigate the Japanese origins and story of Sakuragawa Rikinosuke and Togawa Iwakitchi.

My mother always told me that we had Russian decent as well. I was telling my siblings the other night as my mum would tell me this when I was young and my siblings did not remember.

Hello Danielle

My wife(Tanya) and I have been researching family history for my wife’s grandmother’s(Nana) family tree.

Nana was born “Violet Dulcie Mary Smith” recorded as “Violet Mary Smith” on birth certificate to Samuel Smith and Violet Beatrice Decenoski. (Place of Birth – Harbour View, Cairns”.

We believe your grandmother “Ruby Beatrice” is nana’s sister and would like to ask if you have any photos of nana and her sisters when they were young?

Also, all of the family history references we have read online state that Samuel Smith and Violet Beatrice Decenoski were married but we have been unable to find any marriage records for Samuel and Violet in the QLD, NSW or Victorian BDM database records. Do you have an actual date that they were married, where they were married?

Do you have any actual documentation showing their marriage details?

Thank you Jeff and Tanya

Hi Jeff,

Yes I do have photos I believe and my sister said she and our grandmother Ruby Beatrice went and stayed with your grandmother in NZ many years ago?

So yes we are definitely related!

I would love to get your contact details somehow?

Hello Danielle

I apologize for the late reply

Please send your contact email to mfh1920@outlook.com if you would like to continue to correspond

Thank you Jeff

Hi Steve,

Wonderful story and Thank You for all your efforts and informative research.

My name is Hugh Dicinoski and I am the son of Hugh Ewar Dicinoski 1928 – 1994 ( the son of Reginald and Bridgette ). He was the Brother of Ronald Reginald and sister Zelda.

As a child I spent a great deal of time with Reg ( known to us as Pop ) Bridgette ( known as Nanna ) as well as Goldie and Pearlie.

Reg was a modest and very capable man technically, and in early life owned a bore drilling rig that sunk numerous Water Bores and Windmills for Southern Cross especially in Western Queensland around the Charleville ,Cunnamulla, Thargominda and Noccundra areas.

It would have been a grueling and tough existence as the family all traveled together and effectively lived in the bush.

In later life he became one of the first registered Motor Mechanics in Queensland working out of Faulkner Ford in Toowoomba and finally owning the COR ( later BP ) Service Station and Engineering Workshop in Marburg when the main Brisbane to Toowoomba road ran through the town.

Few people were aware he was a qualified Ju – Jitsu Master and despite being only 5 foot tall was very capable of looking after himself and remained fit and strong into his seventies when sadly his eyesight began to fail him..

Like Ben Mc Innes above I have many fond memories of time spent with him at Baragoola Street in Coorparoo in his pale green Commer Ute ( Ben – I also spent time with Minnie and Neil Mc Innes

( who along with being related ) for a period of time owned the house we lived in at Abbotsford Road at Mayne)

If I could contribute any further information please let me know and Thank You to all contributors as our family also grew up with the belief we were of some style of Russian origin.

Hi Hugh! First, I envy your name that is a legacy of Iwakitchi Togawa (Rikinosuke) – I hope you feel proud of its specific Japanese origins, rather than the vagueness of a Russian or Polish connection. I also envy the fact that you were able to grow up around your grandparents, and Pearlie and Goldie, and get to know them well. Reg sounds like he was a pioneer in a few areas, which, in a way, was a Rikinosuke offspring characteristic.

Please feel free to contribute suitable family stories. As I stated previously, I will endeavour to do my part in the future with efforts to uncover the Japanese side of our family history.

Thanks, Hugh.

Hi Steve, Sakuragawa Rikinosuke and Jane Kerr are my husbands great grandparents on his mother’s side. My husbands mother, Beryl Cook was the daughter of Violet Beatrice Deconoski who’s parents were Sakuragawa Rikinosuke and Jane Kerr.

Hi Kellie,

Your husband and I are related as my grandmother was also the daughter of Violet Beatrice . My grandmother is Beatrice Ruby.

Please pass this onto your husband

Hi Steve ,

I am Zelda Jamieson nee Dicinoski and am the daughter of Ronald Reginald Dicinoski son of Reginald Dicinoski, who was Ewar’s first born son. I have also been very interested in the family history for many years and have written a short story called “Sacanarawa and the Circus” which covers my side of the family. It was good to read what you jhave done also thankyou so much.

Hello, again, Zelda. Thank you for your comment. I would love to read your short story. Talk to you soon.

Wonderful history. My husband is from the Bowtell descendants too so this is so interesting. Thank you

Hello again Steve. I was also told by my husbands grandmother, Phoebe Bowtell/Olsen that she remembered her Aunt Susan and uncle Ewar having a circus. She said her Aunt Sarah, sister to Susan, was married to a showman, Joseph Davis. Sarah, Joseph and their children travelled up and down the east coast of Australia in a covered wagonette drawn by two horses and showing magic lantern slides and later moving pictures. On some occasions, the family joined up with the Dicinoskis and their circus. They each held their own shows.

Hi Julie. Thanks for your interesting insight into family stories. I am aware that Susan was born in Warwick, but her father (John) and mother (Elizabeth) were born in the UK. Indeed, Susan Bowtell was listed as an ‘acrobat’ on her marriage certificate (20 Feb 1892) to Ewar Dicinoski, so it appears that the ‘circus’ gene flowed in both families. It is nice to know that these extended families not only had the same professions, but they were able to share travels and stories as they transversed Australia in their wagons. Fascinating!

Steve, as boys we may have met at your grandfathers 80th birthday at his Westwood home. Reading your posts i also have many fond memories of both Pearl and Goldie. Where do you currently live.?

Hi Gavin. I will respond to you via email. Thanks.