By Shey Dimon

(Read how Shey began her search for her long lost family here)

The email header read, ‘I’ve found your family’.

I think I stopped breathing at that moment. I quickly opened the email.

‘I’ve found him!’ The email from Yuki, my contact at the Wakayama prefectural office, said, ‘his name is Junichi Omae, a 90-year-old man. I just called him right now and talked about how you are looking for him. He knows about your great-grandfather and has his picture. He started crying to hear your story.’

My eyes filled with tears. This was a dream come true. Just before he died, my grandfather, Tom Omaye, gave me his many folders of research on our family tree. He had searched for years for any information about our family in Japan, to no avail. I made a promise to my grandfather, who had passed in 2018, and myself that I would do everything I could to find our relatives. It was now my turn to take over the search.

To make the task extra difficult, our family in Australia spell Omaye with a ‘y’ but in Japan it is just Omae. We didn’t have anything with my great-grandfather’s name written in Japanese, just his English version where he added the ‘y’. He probably did this to make it easier for English pronunciation, but it made the detective work harder.

I had been living in Tokyo for 18 months. In that time, I’d hired a genealogist, checked with the Kainan City office – the city in Wakayama prefecture where my great-grandfather was born – consulted online forums, but all had turned out to be dead ends. Not being able to speak Japanese was holding me back. I needed help.

I learned there would be a conference in Wakayama for people with links to the prefecture in October 2023, so I immediately signed up. I imagined that maybe I would meet someone there who might be able to help me trace my family. It was a long-shot, but worth a try.

And this is how I met Yuki-san at the Wakayama prefectural office, the same Yuki-san who sent me the email about finding Junichi Omae.

She was helping organise this Wakayama Kenjinkai Conference, and I shared my story with her as part of the application process. I also asked her if she knew anyone who might be able to help me find my family. She said she would see, but probably wouldn’t be able to help.

I didn’t know, however, that she was constantly recounting my story to nearly everyone she came across. After repeating my story she would joke, ‘if you meet any Omaes, let me know’.

A journalist she had shared this joke with eventually called her. He had met someone named Omae in Kainan city, where my great-grandfather came from. The journalist had asked this Omae-san if she had a relative who had gone to Australia. She said, no. But… there was one other Omae family she knew of in the city.

Yuki-san made a call to the other Omae family. Ninety-year-old Junichi Omae answered the phone. When Yuki-san told him someone from Australia was looking for relatives in Japan, he started to cry.

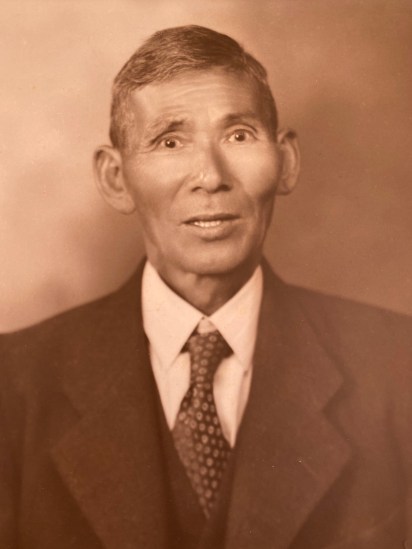

It turns out that Junichi Omae’s grandfather was the brother of my great-grandfather Shojiro, pictured above.

I planned a trip to meet Junichi Omae immediately. The only problem was that he nor his family speak English, and my Japanese is still woeful.

I called a close friend, Etsuko, in Tokyo, who coincidentally also comes from Wakayama Prefecture. She is fluent in English and Japanese. I asked, ‘Etsuko, this is a strange request, but would you consider coming to Wakayama with me to meet my long-lost relatives?’ She said yes without any hesitation, and soon we were on a plane!

Meeting the Omaes

Every time I thought about finally meeting my long-lost family in Japan, my eyes would well up. I had to keep it together. This was so important to me, but I couldn’t help wondering, was it as important to him? Would it be embarrassing being so emotional if he wasn’t?

I had the added pressure of knowing there would be TV crews filming everything. I was hesitant at first when the request came to film the moment of encounter, but my husband convinced me it would be wonderful to have this documented. Not just for me, but for our extended family, and maybe even to inspire others.

We arrived in the pretty town of Kainan, with its narrow streets bordered by a tall, picture-perfect mountain range.

There were six people and two cameras outside Junichi-sama’s house. I could see a casually dressed man in the background, a contrast to the formally dressed TV crew. He was filming everything, and he instantly reminded me of my grandfather Tom, who was always lurking with a video camera. At that time, I didn’t know this man was also a relative!

The initial introduction to the Omae family was stalled as the TV crew considered the best angle to capture the moment. ‘Is this really your first time meeting him?’ they asked. ‘Yes, it really is!’ I replied.

Then I was told to go and hide until they called me.

My friend Etsuko and I stood waiting behind a building taking deep breaths. We were finally called forward.

As we came out of hiding, I found myself standing in front of the kind-eyed Junichi Omae.

I was trying to hold back all my emotions, but my eyes were full of tears. We both bowed deeply and he introduced himself. I nodded, but I couldn’t get any words out. His eyes were full of tears, like mine, and I knew I wasn’t alone in my feelings.

He introduced me to the rest of the family, and I was surprised to learn the man with the camera in the background was Masaitsu, Junichi’s younger brother, who is 81. He really reminded me of my Pop, Tom.

I was also introduced to Shuzo, another of Junichi’s brothers, who is 87, and also Junichi’s daughter, Sayuri.

As I removed my shoes in the entryway, I was amazed by Junichi’s artwork. All the walls were covered in ancient scripts in circles created with acrylic metallic paints. He is incredibly spiritual but also a talented artist, and evidence of this is everywhere in his home.

Sharing stories, photos and gifts

Junichi-sama brought us to a room he’d specially prepared for our meeting, with pictures of his father and grandfather set up. He produced a photograph of my great-grandfather Shojiro, and his daughter Aya, with another unknown man. I had never seen this photo before, but instantly recognised my great-grandfather. He looked smart with his large moustache and neat three-piece suit.

The last time Junichi-sama and his family had heard from my great-grandfather Shojiro was a letter written when Shojiro was interned in Tatura internment camp during WWII. The letter was in English. Maybe the guards only allowed English letters to be sent from the camp. Junichi-sama, who was only a young boy at the time, said they took the letter to the local doctor to translate. All he remembers was that Shojiro said he was interned with his daughter Aya. That was the last they ever heard from him. Junichi-sama said he was so happy to learn that despite the war and internment, Shojiro’s children went on to have happy lives.

Junichi-sama also showed me a portrait of his grandfather, who was my great-grandfather Shojiro’s brother. It turns out there were five children in the family. This was a revelation. We always wondered whether Shojiro had any siblings.

The TV producer asked me why my great-grandfather went to Australia. I said I didn’t know for sure. The producer suggested that maybe he went to earn money for the family because at the time in Wakayama, it was difficult to raise a large family.

I gave Junichi-sama a penny from Shojiro’s coin collection. My daughter had carefully cleaned it with vinegar and salt to bring back its shine. The coin was dated 1933, the year Junichi-sama was born.

I also gave his brothers Masaitsu and Shozo coins from Shojiro’s collection. Masaitsu received a coin from 1941, the year he was born.

Masaitsu’s mother, Tsuneko, was pregnant with him when his father died in Papua New Guinea in WWII. Junichi-sama was then just eight years old. Coincidently, my grandfather Tom and his brother were also deployed to Papua New Guinea around a year later, but with the Australian Army.

Junichi-sama visited Papua New Guinea twice by invitation from the Australian government to visit the memorial to his father. He proudly showed me photos of the Japanese memorial there, right next to the Australian memorial.

He had also visited Brisbane on these trips, and showed me photos of a waterfall he remembered admiring. He said he had wondered whether he would find any of Shojiro’s family while visiting Australia, but he never found us.

Shozo, Junichi-sama’s other brother, was born in 1937. But due to the abdication of King Edward VII that year and the halting of printing the king on the Australian penny, that specific coin is extremely rare and our family did not have one. So I gifted Shozo a 1938 penny instead.

The brothers also had three other siblings who had all passed, including a sister who died when she was only three months old. The family still has her hina doll in remembrance.

Junichi-sama let me to choose one of his paintings to bring home, a famous fabric painting of Kyoto, as well as some beautiful lacquerware, which is famous in Kainan. Masaitsu and his family also gifted me some pottery, more lacquerware, a fan, and more. They were so very generous. Masaitsu explained they were having a lacquerware tray made for me that included our family crest. I was so moved.

I made a photo book for Junichi-sama and surprised him with it. I had spent the few weeks prior to this visit updating the family tree with more old family photos relatives had sent me that I hadn’t seen before.

The last time I had seen most of my extended family in Australia was at my grandfather’s (Tom) funeral in 2018, so meeting Junichi-sama was a great opportunity to connect with them again and also meet new family members I didn’t even know existed. I wanted to make sure everyone knew about this revelation so I could share it with them all.

The photo book I made was full of family tree diagrams, old photos, quotes, memories, and more. Junichi-sama and his family smiled hearing our stories, especially of how my great-aunt Yuki had once sucked red belly black snake venom from my mum’s leg when she was a child, and saved her life!

I also created a video of family members’ messages to Junichi-sama from all around Australia. I included a map of where we are located and a link to Shojiro so he could see in a diagram how we are all related without the need for English descriptions.

In the video, the family members attempted to greet Junichi-sama in Japanese, which I think the Japanese Omae family appreciated! My three-year-old nephew whose middle name is Shojiro made them all laugh with his attempt to pronounce konnichiwa: ‘Ichiwa, Ichiwa…KONichiwa’.

Prayers to our ancestors

Junichi-sama asked if I would like to pray to our ancestors at the family Butsudan or Buddhist altar, and he chanted a prayer while I kneeled beside him. He was very kind, showing me where to put the incense and telling me what to say. I took my time giving thanks for this moment.

Next it was time to visit the Omae family cemetery at the top of the mountain in Kainan City. Junichi-sama jumped on his electric scooter and zoomed off up the road. We all followed and along the way, Masaitsu-sama showed us various houses his family had lived in and a vacant plot of land where their old house burned down.

As we walked through the streets and passed neighbours it was surreal hearing people say, ‘Konnichiwa Omae-san’, my mother’s maiden name.

I asked Junichi-sama if he knew where my great-grandfather had lived, and said he had lived in a house close to the mountain on the edge of Kainan, but unfortunately it was no longer there.

We trekked up to the cemetery. Junichi-sama said it was his first visit in three years as he found walking increasingly difficult. I appreciated the effort he made so we could have this moment together.

Masaitsu-sama showed me how to wash the gravestones and I poured water over the top of them, watching as the water peacefully cascaded over each pillar of the stone. I placed incense in the holder and we prayed again while Junichi-sama chanted. It was one of the most special moments of the day.

The view from the cemetery was incredible. The mountains were misty and it felt like such a profound moment to be all there together. I was so grateful Junichi-sama had struggled up the mountain for this.

He showed me the Omae family crest engraved on the cemetery ornaments: three fans symbolising suehirogari, the opening of a fan to a bright future.

Junichi-sama explained my great-great grandmother was from the Tamaki family in Gobo, Wakayama and her father was the village headman. Next time we meet, we plan to go to Gobo together.

A Kaiseki to remember

Junichi-sama declared it was time to eat, so we drove to a 90-year-old building in town. There, we climbed the three flights of stairs: I held onto Junichi-sama’s arm as we climbed – not that he needed it! He was full of energy that day. We arrived in a private room with a long table and chairs set beautifully.

He explained how he had visited a few restaurants to check the best place for our reunion lunch. The restaurant he’d chosen was absolutely perfect.

He ordered me a beer to celebrate, even though he doesn’t drink alcohol. It was a very sweet moment when he leaned across the table to fill my glass.

See you soon, not goodbye!

We ended the day back at Junichi-sama’s house, where Masaitsu’s daughter, Azusa Ueda, was also waiting to meet us. We talked and shared more stories until it was time to leave.

I will be returning to Kainan with my immediate family in October for the Wakayama Kenjinkai Conference, which made the goodbyes slightly easier.

Instead of bowing goodbye, Junichi-sama held out his hand to shake mine. We both had teary eyes again, and in Aussie style I gave him a big hug, which he welcomed. It was a really lovely moment.

As I turned to leave, I saw a neighbour clapping, and she continued to clap while I said goodbye to everyone, even as we drove away waving.

All day I kept thinking, if only my Pop were here, he would love this moment so much. After I shared all this info with my extended family later on, they all told me Pop would be so proud. Even though he’s no longer with us, I’m happy to say his wish was finally fulfilled.

Now I use Google Translate to communicate with my new-found family via a messaging app. And finding them has inspired me to try harder to learn Japanese.

The local Wakayama TV news featured this special day in their news bulletin on 18 June 2023.

Lastly, a huge thank you to the members of Nikkei Australia. Without this group, I never would have been able to find my relatives. Arigatou Gozaimasu!

All photos supplied by author.

Dear Shey, this is a marvelous and moving family history. Thank you for sharing it publicly. It brought a few tears to my eyes. I hope it inspires others to explore their Japanese heritage.

Enjoy your stay in Japan.

Warmest regards

Andrew Hasegawa

Thanks Andrew! I’m so glad you enjoyed the story and it portrays the emotion of it all.

Such a beautiful reunion! Great story, Shey.

Thanks Christine! Thanks for all your support encouraging me to write my story.

Congratulations Shey on embarking on the journey to find our long lost family in Japan, Your perseverance and determination to the cause was both inspirational and gratifying. What a moving story with a wonderful ending. Thank you to all who assisted Shey in making this possible.

Thanks Mum! Thanks for all your support always. I’m looking forward to your next trip back to Japan and meeting your new relatives!

Thank you Shey for your perseverance in tracking down our Japanese relatives and sharing your meeting experiences. I couldn’t help getting a bit emotional reading your words and living the experience vicariously!

Thanks Ron for also getting involved and telling me your favourite story about your mum Kiyo, a great memory of her making fried rice on the beach with anything she could find, including crab, prawns and even a snake once! I love that story. Those are the stories that keep the memories alive.

Such a fabulous story about connecting with your Japanese family Shey. Really enjoyed this read. Great pics too. Congratulations

Thanks so much Masako! Thanks for your support and interest in our story and encouraging me to share it.

Well done Shey. A beautiful story that brought tears to my eyes.lt is so good to know that we still have living ancestors in Japan.

Thanks once again for all of your hard work and persistence

Thanks Barb! I appreciate all the family coming together to help me piece together the tree for our Japanese relatives. It’s also been lovely reconnecting with you and the other relatives also in this process and hearing all these family stories I didn’t know.

Shey, this is such a touching and emotional story. We always wanted to know more about our relatives in Japan. Thank you for your persistence and dedication in finding them. I look forward to hearing about your reconnection with them in October.

Thanks Simone, it’s been great to connect with you and the rest of the family, one of the many perks of this amazing experience.

Shey, it was wonderful to know more of the history of the Japanese side of our family. Tom would be so proud of all the effort you have put into fulfilling his wishes. I can hear him saying, “I knew she would do it. She’s a smart one that Shey.”

Thanks so much Dawn and thank you for all your help filling in your (Yuki’s) side of the family tree which is huge! It’s been wonderful to connect again and I am so grateful for this whole experience.

Hi Shey , this is a great piece of family history to read , congrats on all your hard work in searching etc. my family wishes all of you over there the very best . My name is Douglas Rohrt ( yuki,s grandson)

Hi Doug, thanks for your comment and I now have your name in the updated tree! Our family is much larger than I ever could have imagined! It’s nice to meet via this story. 🙂